SUITCASE CHARLIE

5 Star Mystery

Recent Review:

This story is gritty--so much so that the scenes I pictured in my head were all in black and white. The crimes are gruesome and not for the faint of heart. The cops are world-weary veterans of WW2, accustomed to the worst humankind has to offer before they begin exploring a depraved series of child murders. John Guzlowski explores the criminal world and tough neighborhoods of 50's era Chicago--a world he knows well. But he also knows the poison of anti-semitism and intolerance.

In Suitcase Charlie he puts the reader on notice that these horrors have survived the war and have followed refugees to Chicago's parks and neighborhoods. The murder of a young black girl is tossed aside like yesterday's newspaper and the lie of the Elders of Zion is alive and well. The detectives must face administrative paralysis and their own growing dread and horror as they try to prevent another murder. I was reminded more than once of M, the brilliant German film about the hunt for a child killer.

Suitcase Charlie is a unique and tightly paced thriller. Mr. Guzlowski has created a world of horrifying crime, tough men and even tougher justice. This novel will not disappoint.

______________

Available from Amazon or Barnes and Noble.

Just click here.

Monday, August 10, 2015

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

A Novel Born of Childhood Nightmares

A Novel Born of Childhood Nightmares

BY SUSAN ELZEY

Special to the

Register & Bee

Danville novelist and poet John

Guzlowski didn’t have to look far for the inspiration for his latest novel

“Suitcase Charlie.” The story was as close as his childhood nightmares.

“We’d laugh, play tag and

hide-and-go-seek, climb on fences, play softball in the nearby park, go to the

corner store for an ice cream cone or a chocolate soda. You name it,” Guzlowski

recalled. “This was the mid-50s at the height of the baby boom, and there were

millions of us kids outside living large and — as my dad liked to say — running

around like wild goats.”

He and his family lived in the

working-class neighborhood of Chicago called “Humboldt Park” or the “Polish

Triangle.” A lot of his neighbors were Holocaust survivors, and Guzlowski and

his friends grew up with the residual fear and anger of their parents, plus the

stories of their parents, all around them.

Guzlowski’s parents had been slave

laborers in Nazi Germany. His mother spent more than two years in forced labor

camps, and his father spent four years in Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Guzlowski was born in a refugee camp in Germany after World War II and came

with his parents, Jan and Tekla, and sister, Donna, to the U.S. as displaced

persons in 1951.

Three

boys murdered

Carefree, that is until the bodies

of three young Chicago boys were found in a shallow ditch after they had seen a

matinee in downtown Chicago.

“Everything changed,” Guzlowski

said. “For the first time, we kids felt the kind of fear outside the house we

had seen inside the house. It shook us up. Where before we hung out on the

street corners and played games till late in the evening, now we came home when

the first street lights came on … The street wasn’t the safe place it once had

been.”

Guzlowski and his friends began

watching for the killer of the boys and even gave him a name — “Suitcase

Charlie” — and imagined that he carried around a suitcase in which he could

haul dead children. Then as the evening shadows fell, a boy would inevitable

look down the street, point and whisper, “Suitcase Charlie?”

It was enough to send the boys

heading for home.

The memories of the murders that

happened when he was 7 stayed with Guzlowski, even if his novel is not about

the murders of those three boys.

His

novel

“The first murder in the novel is

discovered about seven months after those murders. So the detectives in my

novel worry that it may be the same killer,” Guzlowski explained. “They talk

about how the investigation of the Suitcase Charlie murders is or isn’t like the

earlier investigation. Also, people in the neighborhood of the killings wonder

about a connection.”

The summary of the novel on Amazon

reads as follows:

“On a quiet street corner in a

working-class neighborhood of Holocaust survivors and refugees, the body of a

little schoolboy is found in a suitcase.

“The grisly crime is handed over to

two detectives who carry their own personal burdens, Hank Purcell, a married

WWII veteran, and his partner, a wise-cracking Jewish cop who loves trouble as

much as he loves the bottle.

“Their investigation leads them

through the dark corners and mean streets of Chicago — as more and more

suitcases begin appearing. Based on the Schuessler-Peterson murders that

terrorized Chicago in the 1950s.”

Remembering

the Holocaust

He considers “Suitcase Charlie,”

which has some graphic descriptions of violence, an “extension of the horrors

of the Holocaust.”

The Holocaust has been at the heart

of most of Guzlowski’s writing. His book of poetry, “Third Winter of War:

Buchenwald,” was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry in 2007.

“The killer chooses the area because

these people have seen the terrible things that happened during the Holocaust,”

he said.

After he wrote his first book,

“Language of Mules,” Guzlowski’s friend told him that Guzlowski must be “all

Holocausted out,” but that has not been the case. In fact, he a collection of

new poems and short prose pieces he has written in the past 10 years about his

parents that will soon be published by Aquila Polonica, a publishing house that

specializes in publishing works about the Polish World War II experience.

He has recently started writing

science fiction, however, and published a flash fiction post-apocalyptic story.

Selling

‘Suitcase Charlie’

He is also focused on selling

“Suitcase Charlie,” which is available on Amazon.com in both a print edition and

Kindle edition.

What he enjoyed most about writing

the book, though, was revisiting his childhood.

“I enjoyed revisiting all the places

I grew up in,” he said. “The novel begin on the corner of Evergreen Street in

my neighborhood. It was an opportunity for me to revisit Chicago and re-imagine

all the buildings. The cops are interviewing people I knew. It was so much fun

for me.”

Elzey is a freelance writer for the Danville Register & Bee. She can be reached at susanelzey@yahoo.com.

BY SUSAN ELZEY

Special to the Register & Bee

Thursday, July 9, 2015

5 Star Amazon Review

A Review by eBook Review Gal:

Gritty and Good Noir Fiction!

It's 1956 and the city of Chicago is being terrorized by a ruthless killer. Someone is murdering children, draining their blood, chopping them up and stuffing them in suitcases. Hank Purcell is a seasoned detective and WWII veteran, assigned to the case. Along with his trouble-making, heavy drinking partner, Marvin Bondarowicz, the detectives search for clues among the dregs of the city.

John Guzlowski has fictionalized a true-crime story and he's done a fantastic job of it. The subject matter is dark and going noir was probably the best, if not only, way to do it. 1950s Chicago probably had a certain grittiness to it and the characters in this novel definitely reflect that. The author remained true to the era and I appreciated that. I also appreciated the ending - without giving away spoilers, I liked the way book ended. And, although there was a satisfying conclusion, there still remains an opportunity for a sequel(s) involving these two detectives.

I would recommend this book to fans of the noir genre and anyone who enjoys a good whodunit. I'll look forward to more from this author!

eBook Review Gal received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for an honest review.

______________

Suitcase Charlie is available as a Kindle or a paperback from Amazon. Just click here.

Gritty and Good Noir Fiction!

It's 1956 and the city of Chicago is being terrorized by a ruthless killer. Someone is murdering children, draining their blood, chopping them up and stuffing them in suitcases. Hank Purcell is a seasoned detective and WWII veteran, assigned to the case. Along with his trouble-making, heavy drinking partner, Marvin Bondarowicz, the detectives search for clues among the dregs of the city.

John Guzlowski has fictionalized a true-crime story and he's done a fantastic job of it. The subject matter is dark and going noir was probably the best, if not only, way to do it. 1950s Chicago probably had a certain grittiness to it and the characters in this novel definitely reflect that. The author remained true to the era and I appreciated that. I also appreciated the ending - without giving away spoilers, I liked the way book ended. And, although there was a satisfying conclusion, there still remains an opportunity for a sequel(s) involving these two detectives.

I would recommend this book to fans of the noir genre and anyone who enjoys a good whodunit. I'll look forward to more from this author!

eBook Review Gal received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for an honest review.

______________

Suitcase Charlie is available as a Kindle or a paperback from Amazon. Just click here.

Labels:

5 star reviews,

ebook review gal,

guzlowski,

suitcase charlie

Thursday, July 2, 2015

The Business after the Writing

After the Writing the Real Work Begins

My novel Suitcase Charlie was published 2 months ago.

Since then I've become addicted to following the rise and fall of my sales numbers. I get up every morning and the first thing I do is check the numbers. At night before going to sleep, I do the same thing.

Authorrise, a company that provides this info for free, tells me my rank.

Usually it's dropping. In fact for the last 3 days it's been going down, from 75,000 to 150,000 to 400,000. A sad slide. I look at my copies of Suitcase Charlie sitting on my desk, and I shake my head.

This afternoon I got an email from Authorrise. My rank spiked. This is a good thing. Spiking means I've had some sales and my book is getting readers.

In fact, my rank "jumped 227,311 spots from #395,873 to #168,562."

When I first got these spike notes, I was ecstatic. I would jump up and shout, "Holy Smokes!" I'd break out the champagne, even share a glass with my wife Linda.

Now I'm less ecstatic, still happy but no longer crazy, no longer "doing the mambo" ecstatic.

Part of this comes from the realization/discovery what these numbers mean. I've learned that I can go to my author account at Amazon and look at my sales figures.

A 227,311 spike?

Maybe 2 books, maybe 3.

All of this is interesting to me. I've published 4 books of poems and almost never thought about my sales or my rank or whether people were or weren't reading the book. I guess I never felt that poetry had much of a market so never thought of it in terms of sales.

Prose writing has robbed me of my innocence.

__________________

My noir, hardboiled, true to life detective novel Suitcase Charlie is available as a Kindle and a paperback. Buy it, please!

Just click HERE.

My novel Suitcase Charlie was published 2 months ago.

Since then I've become addicted to following the rise and fall of my sales numbers. I get up every morning and the first thing I do is check the numbers. At night before going to sleep, I do the same thing.

Authorrise, a company that provides this info for free, tells me my rank.

Usually it's dropping. In fact for the last 3 days it's been going down, from 75,000 to 150,000 to 400,000. A sad slide. I look at my copies of Suitcase Charlie sitting on my desk, and I shake my head.

This afternoon I got an email from Authorrise. My rank spiked. This is a good thing. Spiking means I've had some sales and my book is getting readers.

In fact, my rank "jumped 227,311 spots from #395,873 to #168,562."

When I first got these spike notes, I was ecstatic. I would jump up and shout, "Holy Smokes!" I'd break out the champagne, even share a glass with my wife Linda.

Now I'm less ecstatic, still happy but no longer crazy, no longer "doing the mambo" ecstatic.

Part of this comes from the realization/discovery what these numbers mean. I've learned that I can go to my author account at Amazon and look at my sales figures.

A 227,311 spike?

Maybe 2 books, maybe 3.

All of this is interesting to me. I've published 4 books of poems and almost never thought about my sales or my rank or whether people were or weren't reading the book. I guess I never felt that poetry had much of a market so never thought of it in terms of sales.

Prose writing has robbed me of my innocence.

__________________

My noir, hardboiled, true to life detective novel Suitcase Charlie is available as a Kindle and a paperback. Buy it, please!

Just click HERE.

Monday, June 29, 2015

Suitcase Charlie -- Chapter 1

Suitcase Charlie is available as Kindle and a paperback from Amazon.

Synopsis: May 30, 1956. Chicago

On a quite street corner in a working-class neighborhood of Holocaust survivors and refugees, the body of a little schoolboy is found in a suitcase.

He's naked and chopped up into small pieces.

The grisly crime is handed over to two detectives who carry their own personal burdens; Hank Purcell, a married WWII veteran, and his partner, a wise-cracking Jewish cop who loves trouble as much as he loves the bottle.

Their investigation leads them through the dark corners and mean streets of Chicago–as more and more suitcases begin appearing.

Based on the Schuessler-Peterson murders that terrorized Chicago in the 1950s.

CHAPTER ONE

There wasn’t any point in hurrying. By the time Hank Purcell and his partner Marvin Bondarowicz got there that night, they couldn’t even get close.

For a block in every direction, it was like a midnight cop convention. The new black-and-white squad cars, with their red lights twirling and lighting up the darkness, were scattered along all the streets leading to the intersection, and a mob of detectives and uniform cops were there, some standing around sweating in the heat, others swarming and going nowhere.

Hank couldn’t imagine what the beef was, why they’d need so many cops. But he had to park the car, so he drove down Rockwell toward Division and finally double-parked a couple blocks south of where the action was. Then he and Marvin started hoofing it back.

When they finally got to the intersection, it was cordoned off.

Hank pulled his handkerchief out of his pocket, wiped his face,and looked around. Yellow police barricades kept the folks who were still awake out of the intersection and on the sidewalks. It was quite a crowd. At the White Eagle Tap, the corner Polack bar,the drunks and third-shift drinkers stood in the doorway, watching the commotion; some had beer bottles in their hands. Kids were sitting on the barricades, craning their necks and bopping up and down to see what was up. The windows in the apartment buildings fronting three of the corners had a few lookers in them, old guys watching and smoking, young girls and women in bathrobes and curlers.

Rubber neckers. Lookie Loos.

Hank wasn’t surprised. He’d seen crowds like this before. At accidents and fires, shootings even. What surprised Hank was that there wasn’t a lot of talking or shouting here. Even when they were pulling bodies out of flipped taxis and burning buses, you could hear some kind of yakking, shouting, crying, moaning even. But there wasn’t anything like that here. All Hank could hear was a low buzz, the kind of human hum he remembered hearing at the ball field when the Cubs were losing, or maybe at a church when the priest was trying to talk the congregation into donating more money so their souls wouldn’t scorch so long in hell. It was that kind of buzz.

Hank wiped the sweat off his neck with his handkerchief and tried to figure out what was going on. Some cops were coming in;some were going out. A darkened ambulance with its back doors swung wide open stood off about twenty feet down Evergreen Street. Three medics stood with their backs to him, but there was enough light from a streetlamp so Hank could see they were smoking. Their heads were together; they were probably talking too.

At the northwest corner where the nuns’ convent stood, Hank saw a half a dozen cops, officers and detectives mostly. They were clustered around something. He spotted his boss, Lieutenant Frank O’Herlihy, on the outskirts of the bunch and poked Marvin’s shoulder.

“Come on.” Hank started across the street, and Marvin followed.

Captain Feltt from the 5th Division, Shakespeare Station, was talking. Hank saw him jerking his head and yammering. The rest of the brass were listening. Feltt was worked up, agitated like he’d just got demoted or shifted over to one of the colored police precincts down on the south side of Chicago, in the Bronzeville section. Hank eased next to him and listened.

Feltt was blabbering the stuff cops always blabber, “Jesus Christ, we’ll get the son-of-a-bitch bastard.” Then Captain Feltt stopped jerking his head and looked down at the sidewalk.

Hank followed his eyes. A brown suitcase lay open on the sidewalk at the Captain’s feet. There was something in it, but Hank couldn’t tell what it was. The shadows of the detectives and the uniform cops clustered around made it difficult for him to figure it out. He wanted to ask but didn’t. Instead, he leaned a little closer and inched his head forward.

Then, he wished he hadn’t.

Hank spun around and threw up into the gutter. The beer he had with Marvin in the alley a while ago was the first to go. Flat and raw, it came up hard. The acid at the bottom of his stomach poured up next, quick as a flush toilet, all hot and burning and twisting his stomach. It was doing what it wanted to do. It churned and brought up just about everything Hank had left in him that wasn’t tied to his insides. Bent over, his hands on his knees, he started coughing and tried to spit the acid out of his mouth and throat.

Marvin was next to him then, holding Hank by his shoulders,steadying him, as his lungs kept hacking and his head kept jerking.

Marvin whispered, “What the hell, Hank, what the hell?”

Hank didn’t say anything, couldn’t say anything. He tried to clear his throat, and he couldn’t do that either. He threw up some more of whatever was left in his guts. Finally, he stood up a little straighter and used his sweat-damp handkerchief to wipe the vomit from his mouth and hands.

“There’s a dead kid in the suitcase,” Hank said.

“A dead kid? You’re crazy, man,” Marvin said as he turned around slowly.

Hank followed him back to the suitcase. Some of the cops had drifted away while he was puking. Others had come up to take their place. Everybody had to take a good, solid look. Get an eyeful. Like there was something here that nobody had ever seen before, some kind of evil that was one-of-a-kind, fresh, and original down to its buttons.

The suitcase was light brown, used but not old, and it wasn’t very large, about two feet by three feet. Big enough to hold a child.

And now Hank could see what he couldn’t see before. The kid in it was a boy not a girl. Hank could tell because the kid was naked: not a stitch of clothes on, and his body was twisted. Arms,feet, shoulders, hands—all twisted up like clean rags. The bones had been broken or chopped up before the body had been shoved into the suitcase. Hank could see that the left foot was pressed against the chin. The head was turned face up, and the right shoulder was placed so that it pointed away from the head.

Hank looked at the boy’s face now. His eyes were staring straight up at him. The mouth hung open in a funny way. Before he stuck the boy in the suitcase, the killer must have broken his jaw.Broken his jaw and drained the blood out of the poor kid. The child was yellow – his face, his feet, his hands, all yellow, the color you get when there’s no blood to keep you alive and pink.

The kid looked like a baby bird that had fallen from a nest in a high tree, a baby bird without feathers.

Hank couldn’t turn away.

“Jesus,” Marvin said as he stared down at the dead child.

Captain Feltt looked at him. “Yeah, Jesus Christ. You gonna puke too, like your pussy friend here?”

Marvin couldn’t say anything except, “Jesus Christ.”

Hank stared some more at the kid in the suitcase and shook his head. He wanted to know why all of the cops were standing around staring at the kid. What kind of sense did that make? They should be out tracking down the killer, pounding him when they found him. Smashing bricks against his head, shoving iron pipes up his ass. He looked at Lieutenant O’Herlihy, his boss. “What do you want us to do?”

O’Herlihy looked at him and said, “Fuck,” and then he didn’t say anything more for a long time.

Hank knew the lieutenant. He was a good man, clean like a boy scout, a church-loving Roman Catholic. He was like the old broads at St. Fidelis up the street who sat in the back pews and mumbled over their rosary beads, a guy who took any kind of looseness as an insult before God, his personal Father. O’Herlihy didn’t appreciate cursing.

So his “fuck” hung in the air between the three men and echoed like a woman’s scream in the dark, repeating itself over and over in pain.

Then the lieutenant shook his head and said, “You know the neighborhood here, Hank. Start talking to people. See if they saw anything tonight. It was hot, so there were lots of people out. See if anybody saw a guy carrying this brown suitcase.”

Hank nodded.

“And when you find him, I want you to hurt him.”

Hank nodded again.

“We’ll hurt him.”

__________________________________

Available as a Kindle or as a paperback. Just click HERE.

Labels:

chicago,

detective,

noir,

peterson,

schuessler,

suitcase charlie,

true crime

Thursday, June 25, 2015

Sweet Home Chicago -- Mayhem in the Polish Triangle

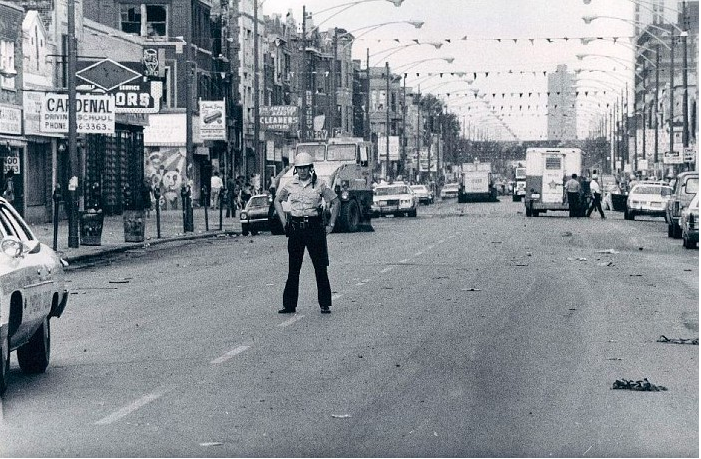

I grew up in a section of Chicago that was called Murdertown in the local papers. This was back in the 50s, 60s, and early 70s.

My friends were beaten, stabbed, pulled from their bicycles and cars and knocked into the street. One of my friends was dragged out of his house by a gang and beaten with clubs until he was unconscious. He was a good boy, kind of sissy-like with long hair and a soft voice but a good boy. He was in the hospital for about a month. He didn’t want to ever leave it.

One time, a man was shot dead in front of my house. When I went outside after the police showed up to see what they were doing, a cop called me a mother fucker and told me he’d throw my ass in jail if I didn't get back home.

I was 12.

I went back into the house and never stepped outside again when someone was shot in front of my house.

I carried a knife, a switchblade, in my pocket. Twice I used it on somebody so that they wouldn't hurt me. Once it was a friend, who was just joking around. He jumped out of an alley way when he saw me passing. I didn't know he was joking, and I stabbed him in the stomach.

When I couldn't get a knife, I carried a hammer or a baseball bat. The hammer was better, lighter, and I could put it in my belt.

Every couple of years there were riots. Mostly in the summer. One time it was so bad that Mayor Daley, the old one, felt the cops needed some back-up so he called in the National Guard. The soldiers drove around the neighborhood in jeeps with loaded machine guns. Nights, you could hear the shooting, see flames rolling off of apartment buildings burning just south of us.

Three of the priests at my old parish St. Fidelis were convicted years later of being pedophiles. They heard my confessions and told me to say three Hail Marys and three Our Fathers. They weren't interested in me. I wasn't pretty enough for them.

One time a gang attacked my mother and me when we were coming home from the supermarket. This was in the early afternoon. It was bright and warm. We were carrying shopping bags, and they wanted to steal our food. We fought them off. My mother beat one of the gang boys down to the sidewalk. He tried to crawl away, but she kept kicking him and kicking him. He pleaded with his homeboys to come save him from my mom. They wouldn't come. They were afraid. Finally, my mother stopped kicking the gang boy, and she let him crawl away.

My mother had survived 2 years of life in a concentration camp, and she knew how to get by in the streets of Chicago, in our old neighborhood.

We finally had to move when the house we had been living in was burned to the ground during a gang war in the early 1970s.

Nobody every rebuilt on that spot. It’s still an empty lot in Murdertown 42 years later.

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Chicago -- Vivian Maier's Vision

When I think about the Chicago I knew as a kid in the 1950s and 1960s, I see images in my memory that remind me so much of the photographs of the great street photographer Vivian Maier.

She moved to Chicago in 1955 and lived there to her death in 2009. During that time she took thousands of photographs, photographs that nobody saw until after her death.

When I first saw them, I felt a bond with her. She saw the streets I saw as a kid. While writing Suitcase Charlie, I often turned to the sites on the internet that housed her photographs. They were an inspiration.

Here's a small gathering of her photos.

______________________

If you want to see more of her photographs, one of the best sources is the Maloof collection of her work. It's online and free. Just click here.

She moved to Chicago in 1955 and lived there to her death in 2009. During that time she took thousands of photographs, photographs that nobody saw until after her death.

When I first saw them, I felt a bond with her. She saw the streets I saw as a kid. While writing Suitcase Charlie, I often turned to the sites on the internet that housed her photographs. They were an inspiration.

Here's a small gathering of her photos.

______________________

If you want to see more of her photographs, one of the best sources is the Maloof collection of her work. It's online and free. Just click here.

Labels:

chicago,

detective,

noir,

suitcase charlie,

true crime,

vivian maier

Saturday, June 20, 2015

The Schuessler-Peterson Murders, Chicago 1955

My novel Suitcase Charlie begins with a Prologue, a statement from an Associated Press wire report from October 18, 1955.

The bodies of three boys were found nude and dumped in a ditch near Chicago today at 12:15 p.m. They were Robert Peterson, 14, John Schuessler, 13, and brother Anton Schuessler, 11.

They had been beaten and their eyes taped shut. The boys were last seen walking home from a downtown movie theater where they had gone to see “The African Lion.”

As I wrote in my recent essay “Suitcase Charlie and Me,” the murder of the Schuessler brothers and Bobby Peterson is at the heart of my novel Suitcase Charlie. It’s what terrified me as a kid and haunted a lot of the other kids I grew up with. Until we got older and went to high school and learned that fearing something isn’t cool, we feared stuff, and one of the fears we most felt was the fear of the person who killed John, Anton, and Bobby.

There’s not a lot actually about their murders in Suitcase Charlie. The first murder in the novel is discovered about seven months after the Schuessler-Peterson murders. So the detectives in my novel worry that it may be the same killer. They talk about how the investigation of the Suitcase Charlie murders is or isn’t like the earlier investigation. Also, people in the neighborhood of the killings wonder about a connection. Like I said, there’s not a lot about the earlier murders in my novel. My novel isn’t about them.

But I know some readers are interested in the Schuessler-Peterson case. They’ve asked me about the novel’s Prologue, so I’m going to talk a little about the case that inspired my novel.

The day the boys disappeared, Sunday, October 16, 1955, they were seen in a number of places: some buildings downtown in the Loop and some bowling alleys near their home on Montrose Avenue. The cops figured that after seeing the movie The African Lion the boys hung out downtown until about 6 pm, wandering around, seeing stuff, probably doing the kind of goofing around I talk about in my “Suitcase Charlie and Me” essay. They were spotted on Montrose at a bowling alley around 7:45 pm. One of the men working there said some older guy was talking to them, some guy who seemed friendly. The boys left a little while later and started walking and hitching down Montrose Avenue toward home.

They were last seen alive about 3 miles away, getting into a car near the intersection of Lawrence and Milwaukee. That was at 9:05 that night.

Two days later, on Tuesday, October 18, their bodies were discovered outside the Chicago city limits, in a ditch in the Robinson Woods Forest Preserve, near the Des Plaines River.

A liquor salesman was taking his lunch in a parking lot there that day. When he looked up from his sandwich, he saw what he thought was a manikin. It turned out to be the body of a young boy, naked with his eyes and mouth taped shut with adhesive tape. Near him were two other naked bodies with eyes and mouths taped. All three boys had died the same way, asphyxiation.

What followed was one of the most extensive investigations in the history of the Chicago Police Department. Between the date the boys’ bodies were found and 1960 when the Chicago Tribune ran an article updating this cold case, more than 44,000 people with some kind of information about the murders were interviewed. More than 3,500 suspects were questioned.

What followed was one of the most extensive investigations in the history of the Chicago Police Department. Between the date the boys’ bodies were found and 1960 when the Chicago Tribune ran an article updating this cold case, more than 44,000 people with some kind of information about the murders were interviewed. More than 3,500 suspects were questioned.

None of it led to the discovery of the killer of the 3 boys.

However, what did follow were some additional murders, ones that seemed to share similarities with the Schuessler-Peterson case.

December 28, 1956, a little over a year after the Schuessler-Peterson murders, two young sisters, Barbara, 15, and Patricia 13, went to the Brighton Theater on Archer Avenue to see an Elvis Presley movie, Love me Tender. Four weeks later, on January 22, 1957, their naked bodies were found behind a guard rail on a country road in an unincorporated west of Chicago. Their bodies like those of the Schuessler-Peterson boys had apparently been thrown out of a car. Unlike the boys, the girls had not died of asphyxiation. Their deaths were thought to have been caused by secondary shock due to exposure. The investigation into the cause of their deaths led nowhere.

Over the years, a number of other murders in the area have been linked to the Schuessler-Peterson killings. John Wayne Gacy, the notorious “Killer Clown” guilty of murdering at least 33 young boys, was suspected by Detective John Sarnowski, one of the detectives working the Schuessler-Peterson cold case, of possibly being involved with the murders of John, Anton, and Bobby. Brach Candy Heir, Helen Brach was also linked with the Schuessler brothers and Bobby Peterson. She disappeared in February 1977 and was declared legally dead in 1984. One of the suspects in this case was a racketeer and stable owner Silas Jayne, a man also for a while a suspect in the deaths of the Grimes Sisters.

So who killed the Schuessler boys and their friend Bobby Peterson?

The best guess is Kenneth Hansen.

His name came up during a Federal investigation in the early 1990s of arson in horse racing stables around Chicago. A number of the people being investigated told the Federal authorities that Hansen had repeatedly over the years spoken about his involvement with the killing of John, Anton, and Bobby. Prosecutors at the trial proved that Hansen picked up the boys while they were hitching, abused two of them, and then killed all three when they threatened to tell their parents. He was sentenced to 200-300 years for his crimes and died in prison in September 14, 2007.

For those people who like to re-work old crimes, there are a number of interesting facts here that should get them going:

- Hansen worked at Idle Hour Stables. That’s where the killing of the three boys took place.

- Silas Jayne, who I mentioned earlier, was the owner of the Idle Hour Stables at the time.

- Later he was a suspect in the Grimes Sisters’ murder.

- Hansen was also a suspect in the Helen Brach disappearance.

- Recently, a former head of the Cook County Sheriff’s Police has offered the theory that Hansen might have been involved in the disappearance or death of the Grimes Sisters.

If you’re interested in finding out more about these murders, doing your own preliminary detective work, a good place to start is the Chicago Tribune’s extensive online archives. They are free and easy to use and will keep your eyes going for a long time. Just Google http://archives.chicagotribune.com and put in your search phrase.

Here are some of the archival articles I found especially important. Just click on the titles.

The Trial of Kenneth Hansen.

____________

The novel Suitcase Charlie is available from Amazon as a kindle and a paperback. Just click HERE.

_____________

_____________

The third image above is by Vivian Maier, the great urban photographer. The other photos are archival.

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

Suitcase Charlie and Me -- How I Came to Write Suitcase Charlie

Suitcase Charlie and Me

I started writing my novel Suitcase Charlie about sixty years ago when I was 7 years old, just a kid.

At that time, I was living in a working-class neighborhood on the near northwest side of Chicago, an area sometimes called Humboldt Park, sometimes called the Polish Triangle. A lot of my neighbors were Holocaust survivors, World War II refugees, and Displaced Persons. There were hardware-store clerks with Auschwitz tattoos on their wrists, Polish cavalry officers who still mourned for their dead comrades, and women who had walked from Siberia to Iran to escape the Russian Gulag. They were our moms and dads. Some of us kids had been born here in the States, but most of us had come over to America in the late 40s and early 50s on US troop ships when the US started letting us refugees in.

As kids, we knew a lot about fear. We heard about it from our parents. They had seen their mothers and fathers shot, their brothers and sisters put on trains and sent to concentration camps, their childhood friends left behind crying on the side of a road. Most of our parents didn’t tell us about this stuff directly. How could they?

But we felt their fear anyway.

We overheard their stories late at night when they thought we were watching TV in a far off room or sleeping in bed, and that’s when they’d gather around the kitchen table and start remembering the past and all the things that made them fearful. My mom would tell about what happened to her mom and her sister and her sister’s baby when the German’s came to her house in the woods, the rapes and murders.

You could hear the fear in my mom’s voice. She feared everything, the sky in the morning, a drink of water, a sparrow singing in a dream, me whistling some stupid little Mickey Mouse Club tune I picked up on TV. Sometimes when I was a kid, if I started to whistle, she would ask me to stop because she was afraid that that kind of simple act of joy would bring the devil into the house. Really.

My dad was the same way. If he walked into a room where my sister and I were watching some TV show about World War II – even something as innocuous as the sitcom Hogan’s Heroes – and there were some German soldiers on the screen, his hands would clench up into fists, his face would redden in anger, and he would tell us to turn the show off, immediately. Normally the sweetest guy in the world, his fear would turn him toward anger, and he would start telling us about the terrible things the Germans did, the women he saw bayoneted, the friends he saw castrated and beaten to death, the men he saw frozen to death during a simple roll call.

This was what it was like at home for most of my friends and me. To escape our parents’ fear, however, we didn’t have to do much. We just had to go outside and be around other kids. We could forget the war and our parents’ fear with them. We’d laugh, play tag and hide-and-go-seek, climb on fences, play softball in the nearby park, go to the corner story for an ice cream cone or a chocolate soda. You name it. This was in the mid 50s at the height of the baby boom, and there were millions of us kids outside living large and – as my dad liked to say – running around like wild goats!

(photo by Vivian Maier)

In the streets with our friends, we didn’t know a thing about fear, didn’t have to think about it.

That is until Suitcase Charlie showed up one day.

It happened in the fall of 1955, October, a Sunday afternoon.

Three young Chicago boys, 13-year old John Schuessler, his 11-year old brother Anton, and their 14-year old friend Bobby Peterson, went to Downtown Chicago, the area called the Loop, to see a matinee of a Disney nature documentary called The African Lion. Today, the parents of the boys probably would take them to the Loop, but back then it was a different story. Their parents knew where they were going, and the mother of the Schuessler boys in fact had picked out the film they would see and given the brothers the money to pay for the tickets. At the time, it wasn’t that unusual for kids to be doing this kind of roaming around on their own. We were “free-range” kids before the term was even invented. Every one of my friends was a latch key kid. Our parents figured that we could pretty much stay out of trouble no matter where we went. We’d take buses to museums, beaches, movies, swimming pools, amusement parks without any kind of parental guidance. There were times we’d even just walk a mile to a movie to save the 10 cents on the bus ride. We’d seldom do this alone, however. Kids had brother and sisters and pals, so we’d do what the Schuessler brothers and their friend Bobby Peterson did.

We’d get on a bus, go downtown, see a movie and hangout down there afterward. There was plenty to do, and most of it didn’t cost a penny: there were free museums, enormous department stories filled with toy departments where you could play for hours with all the toys your parents could never afford to buy you, libraries filled with books and civil war artifacts (real ones), a Greyhound bus depot packed with arcade-style games, a dazzling lake front full of yachts and sailboats, comic book stores, dime stores where barkers would try to sell you impossible non-stick pans and sponges that would clean anything, and skyscrapers like the Prudential Building where you could ride non-stop, lickety-split elevators from the first floor to the 41st floor for free. And if you got tired of all that, you could always stop and look at the wild people in the streets! It was easy for a bunch of parent-free kids to spend an afternoon down in the Loop just goofing off and checking stuff out.

Just like the Schuessler Brothers and their friend Bobby Peterson did.

But the brothers and Bobby never made it home from the Loop that Sunday in October of 1955.

Two days later, their dead bodies were found in a shallow ditch just east of the Des Plaines River. The boys were bound up and naked. Their eyes were closed shut with adhesive tape. Bobby Peterson had been beaten, and the bodies of all three had been thrown out of a vehicle. The coroner pronounced the cause of death to be “asphyxiation by suffocation.”

The city was thrown into a panic.

For the first time, we kids felt the kind of fear outside the house we had seen inside the house. It shook us up. Where before we hung out on the street corners and played games till late in the evening, now we came home when the first street lights came on. We also started spending more time at home or at the homes of our friends, and we stopped doing as many things on our own out on the street: fewer trips to the supermarket or the corner store or the two local movie theaters, The Crystal and The Vision. The street wasn’t the safe place it once had been. Everything changed.

And now we were conscious of threat, of danger, of the type of terrible thing that could happen almost immediately to shake us and our world up.

We started watching for the killer of the Schuessler Brothers and Bobby Peterson. We didn’t know his name or what he looked like, nobody did, but we gave him a name and we had a sense of what he might look like. We called him Charlie, and we were sure he hauled around a suitcase, one that he carried dead children in. Just about every evening, as it started getting dark, some kid would look down the street toward the shadows at the end of the block, toward where the park was, and see something in those shadows. The kid would point then and ask in a whisper, “Suitcase Charlie?”

We’d follow his gaze and a minute later we’d be heading for home.

Fast as we could.

______________________

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)